Nobody likes to fail. I certainly don’t. The fear of failing again has stayed with me ever since we canceled our Kickstarter campaign three years ago — the one this website was named for.

We canceled it for several good reasons:

- Our seed funder’s check bounced.

- The marketplace had changed, making custom WordPress theme design and web design far less important to users.

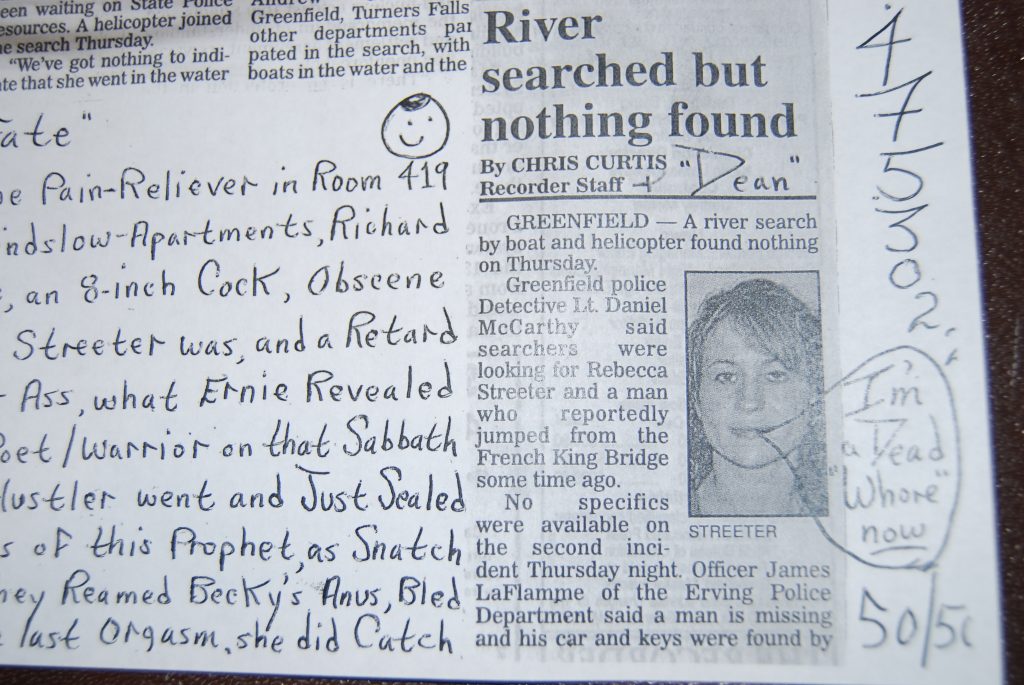

- I received a disturbing and threatening package dropped outside my office door, just a few days after an article ran about us in the local paper.

I had three women working with me at the time — one an intern barely out of her teens. If it was just me, maybe I would have soldiered bravely on. But I was worried about putting others at risk. I reached out to my small town community in shock, hoping for support and solidarity. Nobody gave much of a fuck. Big surprise. I don’t live there any more.

So I moved on to a different project.

We got interest in our new idea, but we were nearly out of money. There was only one thing left to do. I turned my hand back to the old, boring web development business. We got that going on — carved out a new niche for ourselves helping other entrepreneurs ramp up. Ironic, no?

I thought it was about time I got back to coding, having taken a year and a half off to chase startup dreams. I did a little demo in Swift. I showed it to some people. And it blew my mind. Folks were actually interested. Money we had been promised in 2013 finally materialized.

And… the rest is present.

We built a cool thing.

We did it for a shoestring budget, even given the funding we got. I was typically the one who skipped a paycheck if things got lean. It’s a chick thing, I guess–you skip meals so your children don’t go hungry.

For me, it was always worth it.

I absolutely love my job. It’s the ride of a lifetime, and I’d give anything to keep doing it.

The problem is, one way or another — it’s about to change.

Once we bring VC in, we lose control of what we’ve built. I have to remind anyone reading this that I don’t have a Series A yet — but I am optimistic we can get there. More to the point, if we go down that route and we are offered a deal, we will most certainly take it. This is one of the last moments where I can bow out without being a total dick to everyone else on the team.

I’ve talked to a lot of friends in the Privacy/Encryption/FOSS community, and they’re all like, “Do what you have to do, man. Take the money and run.”

It’s not a matter of idealism for me.

It’s more a matter of artistic integrity, I guess, if I want to sound really pretentious about it. I don’t care so much about changing the world. I just want to build cool stuff.

I know the projects I would work on. At least the first six.

What’s stopping me? I’d be broke as shit, for one. But mostly, I’m not sure anybody would notice or care. At least if I take the money, I get my picture in the news a few times. Maybe I’d have some kind of platform to influence matters.

So Where Does That Leave Us?

I still haven’t made up my mind. I probably won’t tell anyone when I do. But I know my own break points. There is really only one secret to success: structure your choices so that two or more likely outcomes result in a win.

Check. Mate.

Technology was an omnipresent theme at BIEN 2016, and also the subject of debate. Profs. Inoue, Shinagawa, and Tsuzuki analyze the economic impact of artificial intelligence on employment. Guy Standing may argue that the movement does not need the specter of future job loss caused by automation, but it remains a compelling vision, as evidenced by the “friendly robots” demonstrating in Davos and on behalf of the Swiss referendum. Yet technology is not the enemy, or even a neutral force.

Technology was an omnipresent theme at BIEN 2016, and also the subject of debate. Profs. Inoue, Shinagawa, and Tsuzuki analyze the economic impact of artificial intelligence on employment. Guy Standing may argue that the movement does not need the specter of future job loss caused by automation, but it remains a compelling vision, as evidenced by the “friendly robots” demonstrating in Davos and on behalf of the Swiss referendum. Yet technology is not the enemy, or even a neutral force.